The 12 people on the jury for Roderick Sutherland’s trial are deliberating their verdict.

He is the last of nine people who faced charges in connection with Megan Gallagher’s murder on Sept. 20, 2020 — although he did not face trial for murder, but for manslaughter, unlawful confinement and offering an indignity to human remains. He pleaded not guilty.

Gallagher was murdered after being confined and assaulted in a Saskatoon garage. Her remains were found on the bank of South Saskatchewan River, about 105 kilometres northeast of Saskatoon, near the village of St. Louis, on Sept. 29, 2022.

With the jury now sequestered, this means publication bans tied to evidence, agreed statements of facts and victim impact statements from earlier trials and sentencing hearings are no longer in force — including details about the other individuals who were charged and their court outcomes that the jurors didn’t learn.

Robert (Bobby) Thomas was the first person charged with murder, on Sept. 20, 2022. He pleaded guilty in October 2024 to second-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 18 years. It stands as the only murder plea of the nine accused and the only murder charge that the jury knew about.

Cheyann Peeteetuce and Summer-Sky Henry were both charged with first-degree murder, but pleaded guilty to manslaughter in January 2025 and were sentenced to seven years each.

Ernest Vernon Whitehead, Jessica Badger (Sutherland) and John Wayne Sanderson pleaded guilty to offering an indignity to human remains. Charges against Robin John (unlawful confinement and aggravated assault) and Thomas Sutherland (manslaughter) were stayed.

The jury also wasn’t told that Roderick Sutherland was initially charged with first-degree murder, but in August 2025 the charge was downgraded to manslaughter. That fact was available online, but jurors were instructed not to conduct their own searches for information.

There were also developments and facts during this trial — that happened when the jury was not present — that could not be reported until Crown prosecutors Bill Burge and Jennifer Schmidt and defence lawyers Blaine Beaven and Alora Arnold closed their cases and Justice John Morrall gave his instructions to the jury.

On Thursday, he spent two-and-a-half hours reviewing evidence from the trial and explaining the law around the three charges to jurors, before they were sequestered to begin their deliberations.

What follows are some of the points the jury did not hear.

The Gallagher hoodies

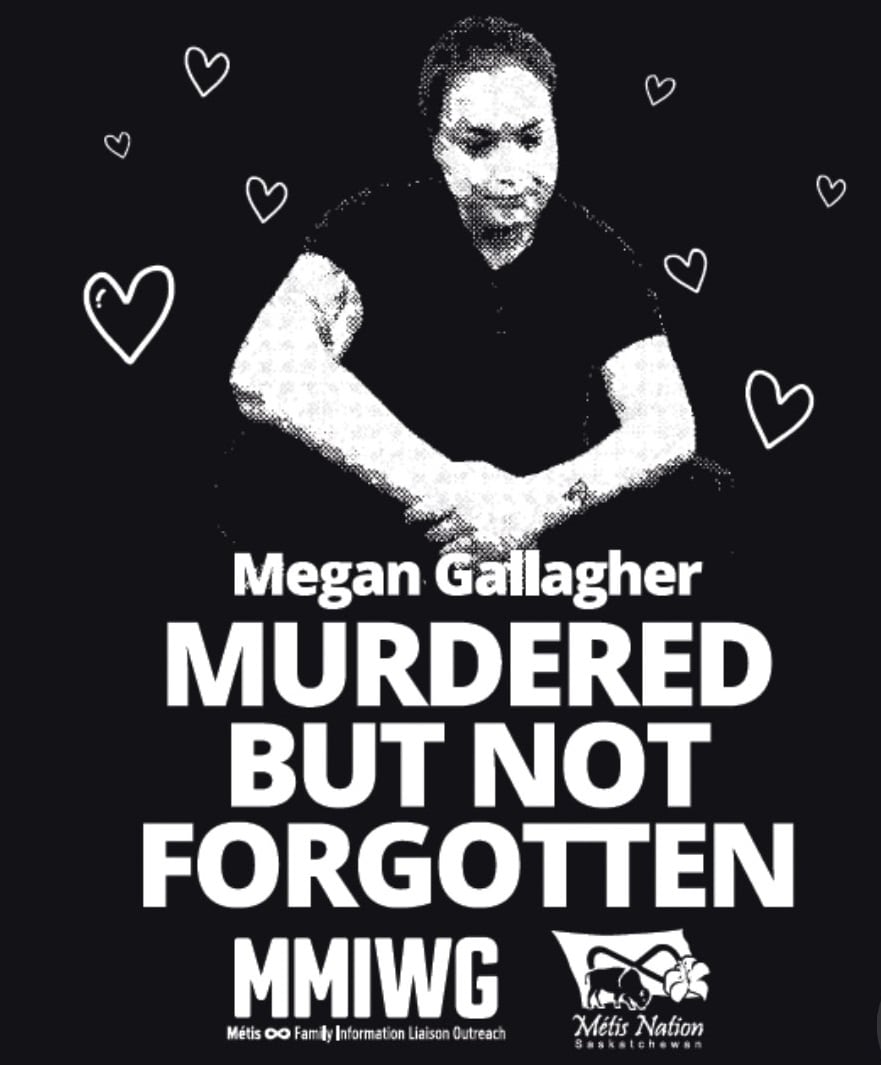

On the third day of the trial, Beaven asked the judge to instruct Gallagher’s friends and family in the gallery to stop wearing black hoodies emblazoned with a photo of Megan and large text that said, “murdered but not forgotten.”

The clothing, worn by people in proximity to the jurors, would either intimidate jurors or send a false message about murder during a manslaughter trial, Beaven argued.

He asked that they turn their hoodies inside out that day, and then refrain from wearing them in the future.

The family disagreed, saying that a deputy sheriff had said they could wear them during the trial but not during jury selection. They also wanted clarity on whether they could wear shirts honouring Missing and Murdered Women and Indigenous Girls.

Morrall ordered that the shirts with Megan’s photo and the “murdered” text not be worn. In the following days, family and supporters wore red shirts — the colour chosen because it is believed to call back the spirits of the missing and represent their lifeblood.

Criminal records

Jurors heard from Cheyann Peeteetuce, who pleaded guilty earlier this year to manslaughter. She was questioned on the stand about her role in Gallagher’s death, and what she knew of Roderick Sutherland.

Jurors heard that she had pleaded guilty to manslaughter — but knew little about the rest of her significant criminal record. Nor did they know that she had been originally charged with first-degree murder in Gallagher’s death.

In 2015, Peeteetuce pleaded guilty to two counts of dangerous driving causing death after killing two teenagers in a crash in Saskatoon. Police said she was impaired at the time and drove a stolen truck through a stop sign, hitting another vehicle.

She was a member of the Indian Posse street gang at the time. She was sentenced to six years in prison, and served four years.

The ‘Vetrovec warning’

The Crown and defence closed their cases on Oct. 14, after prosecutor Burge told jurors that police were not able to find their final witness — Ernest Whitehead — and defence lawyer Blaine Beaven chose not call any witnesses.

Justice Morrall then dismissed the jury so he could discuss with the lawyers whether he should issue a “Vetrovec warning” to the jurors as part of his charge.

The name comes from a 1982 Supreme Court of Canada case. The warning refers to the degree to which a judge should caution the jury about believing an “unsavoury or untrustworthy” witness. The caution is that it would be dangerous to convict an accused solely on the witness’s evidence.

Both Burge and Beaven agreed the potential warning should not apply to Peeteetuce because, by their assessment, she did not offer any practical evidence in her testimony — she testified she could not, for instance, recall why she had pleaded guilty to manslaughter.

They did disagree, however, on whether the judge should warn the jury about the testimony of Robert (Bobby) Thomas, who admitted on the stand to lying to police and to being on a methamphetamine bender when Gallagher was murdered.

Thomas had, for example, lied about knowing Gallagher.

Burge said that Thomas’s testimony did not warrant a warning. Thomas pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and is a serving prisoner so, although he may be “unsavoury,” Burge said Thomas had nothing to gain personally by telling anything but the truth about what happened.

Beaven argued that the judge should give the warning.

He noted that, although it would be dangerous to convict Sutherland on Thomas’s evidence alone, the judge should also point out the evidence in his testimony that could be confirmed by other witnesses, such as the drug use by the people in the garage.

In his charge Thursday, Morrall did issue a warning concerning Thomas — specifically advising the jurors to approach his testimony “with the greatest care and caution” because of his admitted history of lying to the police and in court.

He urged jurors to look for independent evidence to confirm his testimony. For instance, he said bank records from the convenience store show that Gallagher came and went from the garage in the early stages, which could confirm Thomas saying things were “fine” before turning violent.

The ‘abandonment’ defence

Beaven also argued that he should be able to present the jury the defence of “abandonment.”

Sutherland had tried to remove himself from the situation when he saw that Gallagher had been tied up in the garage, Beaven said. As such, he had “abandoned” her unlawful confinement.

Burge argued that Sutherland did not comply with what constitutes abandonment because he could have left the garage, or he could have called the police.

Morrall ruled that abandonment could be presented to the jury as a possible defence.